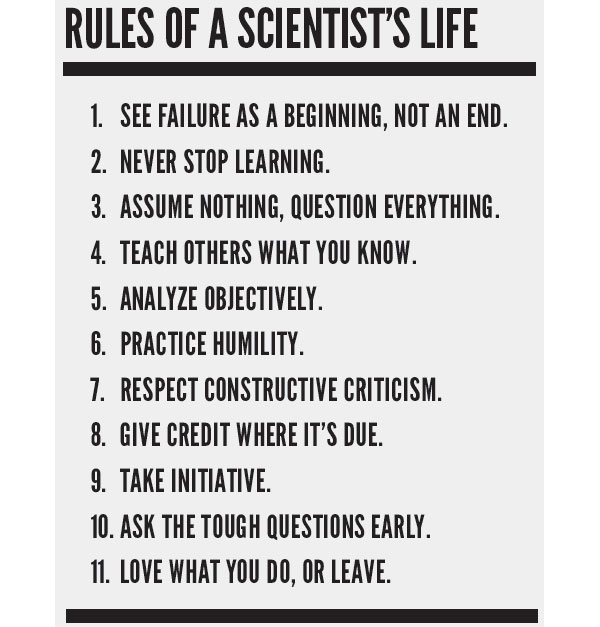

Alan Marnett published eleven “Rules for a Scientist’s Life” in 2013. It’s a good list that can be applied to entrepreneurs as well.

Rules of a Scientist’s Life, Applied to Entrepreneurs

Alan Marnett wrote the following short blog post in early January 2013:

Alan Marnett wrote the following short blog post in early January 2013:

We’re three weeks into the new year. By now, most of us have decided that the “all organic raw nuts and berries” diet we were so gung ho about probably isn’t going to make it into February. Nor is the six-days-a-week workout schedule we undertook on January 2nd, after the hangover wore off. For now, three days a week will do. By March, we won’t even remember which gym we signed up with. Reflecting upon the over-optimistic personal goals we set for ourselves every January, we pondered whether their were rules of a scientist’s life that we should adhere to at all times, regardless of the month.

Rules of a Scientist’s Life by Alan Marnett (2013)

And included the following list of “Rules of a Scientist’s Life.”

- See failure as a beginning, not an end.

- Never stop learning.

- Assume nothing, question everything.

- Teach others what you know.

- Analyze objectively.

- Practice humility.

- Respect constructive criticism.

- Give credit where it’s due.

- Take initiative.

- Ask the tough questions early.

- Love what you do, or leave.

I was impressed with these rules. This image has been reproduced in many places and ascribed to several famous scientists, but I wanted to give credit where it was due. I spent some time to confirm that Alan Marnett is the author and his blog post is the earliest place the image and the rules as a set can be found on the net.

Applying “Rules of a Scientist’s Life” to Entrepreneurship

See failure as a beginning, not an end. You can always learn something from failure-it’s often more instructive than success. Failure can tell you that your old techniques and rules of thumb no longer apply: you must see things as they are and make a fresh start. If you see failure as an end, you can fall into the trap of persisting in an unworkable approach instead of admitting to yourself the need to start over.

Never stop learning. Learning is a wonderful remedy for managing the ups and downs of the entrepreneurial roller coaster. Curiosity is a much better frame of mind to cultivate than recrimination or self-doubt. Making connections between different things that you have learned is a good way to solidify your understanding. The trap to avoid is hunkering down in the library or never leaving the classroom. You have to apply what you have learned, or at least make an attempt to apply it. This will further solidify your understanding.

Assume nothing, question everything. While it’s important to remember that many things you know may be wrong, it’s also important to stand on the shoulders of giants and assume many things are correct.

Teach others what you know. Don’t hoard information and expertise, but be careful that your potential pupils are actually asking for your insights–or are at least receptive to them. Questions that unlock someone else’s curiosity are frequently more instructive than giving the answer, especially if it allows your student to infer a general rule or model instead of taking your specific answer and moving forward with a more global understanding.

Analyze objectively. This is one mode to make sure you apply. We cannot help but have an initial emotional reaction and intuitions about a particular situation. The challenge is to complement those with a more thorough objective analysis. Some of the hardest things to analyze are commonplace items and events because your initial reaction can be to gloss over them without any analysis at all.

Practice humility. If only because it takes a long time to get good at an appropriate level of humility.

Respect constructive criticism. Offer thanks and explain how you plan to act on or incorporate this criticism into your actions going forward.

Give credit where it’s due. It’s easy as a leader to take credit for a team’s actions or firm success. It’s far more empowering and energizing to share it liberally. Make sure that managers under you are also identifying strong performance at both an individual and a team level.

Take initiative. Act when the time is ripe and you have a clear understanding. Please note that “clear” is not the same as “complete.” In competitive situations, you often have to act with only half to two-thirds of the information you would need to be certain. But waiting for complete understanding will cede the initiative. The need to seize the initiative is critical in rapidly deteriorating situations: don’t wait to see how bad it can be, start your mitigation and recovery efforts as soon as you recognize it.

Ask the tough questions early. Start with a hard look at your own motives, shortcomings, and true capabilities. Then involve other people to gain a clear understanding of constraints, possible courses of action, intermediate and final objectives, and likely failure modes and consequences. Candor and tough questions all around are the fastest way to bring a team together and get them moving toward a viable solution.

Love what you do, or leave. The only way to succeed as an entrepreneur is to follow your passion. This does not mean you have to love all–or even most–aspects of solving a particular problem! But you do have to love the problem and be motivated by the benefit it brings to those affected by it.

“True learning involves figuring out how to use what you already know in order to go beyond what you already think.”

Jerome Bruner in In Search of Mind: Essays in Autobiography.

Related Blog Posts

- A World Built by Scientists and Engineers But Run by Salespeople

- Q: Forming a Scientific Advisory Board

- Working in Silence

- Constructive Pessimism

- Citizen Science: An Open Source Model For Collaboration

- Think Twice Before Saying

- Am I Making A Fool Of Myself?

- The Unreasonable Entrepreneur

- Janet Iwasa: Animate Your Hypothesis to Explore Its Viability and Implications

- Sidney Brenner: The Trouble with American Science

- Rules of a Scientist Life (PDF of Rules from Benchfly.com)

Image Credit: Rules of a Scientist’s Life by Alan Marnett