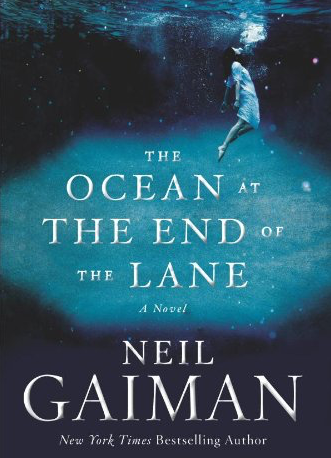

“The Ocean at the End of the Lane” is an autobiographical fantasy novel written by Neil Gaiman in 2013. He explores how we carry the lessons of childhood and the wisdom of a seven year old with us throughout our lives.

The Ocean at the End of the Lane

This is a book review post and a Father’s Day post. I have combined an analysis of some lessons from childhood Gaiman suggests with memories of my own childhood.

This is a book review post and a Father’s Day post. I have combined an analysis of some lessons from childhood Gaiman suggests with memories of my own childhood.

- We are all children, but some of us dress as adults.

- Adults follow paths, children explore.

- Childhood friendships are pure sense of safety and belonging.

- As we age we become our parents.

- Boys almost instinctively reach for a ball.

- Our reach exceeds our grasp: an artist’s vision extends beyond the world we know.

We Are All Children,

But Some Dress As Adults

The Ocean at the End of the Lane captures the pain and confusion and simpler understanding of the world we have when we are seven. Told from the perspective of an artist in his 40s returning to his childhood home for the funeral of a parent.

“I wore a black suit and a white shirt, a black tie and black shoes. All polished and shiny; clothes that would normally make me feel uncomfortable, as if I were in a stolen uniform., or pretending to be an adult. Today they gave me a comfort of a kind. I was wearing the right clothes for a hard day.

[…]

I got in my car and I drove, randomly, without a plan, with an hour or so to kill before I met more people I had not seen for years and shook more hands and drank too many cups of tea from the best china.” “

This theme of a child inside an adult or wearing a uniform to assume a role recurs several times (the narrator later observes, “One of the men told me he was a policeman, but he wasn’t wearing a uniform, which I thought was disappointing: if I were a policeman, I was certain, I would wear my uniform whenever I could.”). In this case, he recognizes the value of tradition, where, in the presence of tremendous emotional stress, you don’t have to come up with a new or creative solution. The phrase “drank too many cups of tea from the best china” captured the reciprocal obligations of the grieving and those seeking to comfort them.

Later, he recalls a conversation with Lettie Hempstock, in which she states the theme more directly.

“I’m going to tell you something important. Grown-ups don’t look like grown-ups on the inside either. Outside, they’re big and thoughtless and they always know what they’re doing. Inside, they look just like they always have. Like they did when they were your age. The truth is, there aren’t any grown-ups. Not one, in the whole wide world.”

He reflects on this and comes up with a metaphor that is more accurate: the child exists buried in the adult.

“We sat there, side by side, on the old wooden bench, not saying anything. I thought about adults. I wondered if that was true: if they were all really children wrapped in adult bodies, like children books hidden in the middle of dull, long books. The kind with no pictures or conversations.”

Adults Follow Paths, Children Explore

“Adults follow paths. Children explore. Adults are content to walk the same way, hundreds of times, or thousands; perhaps it never occurs to adults to step off the paths, to creep beneath rhododendrons, to find the spaces between fences. I was a child, which meant that I knew a dozen different ways of getting off our property and into the lane, ways that did not involve walking down the drive.”

The ability to remain curious as an adult, to ask “stupid questions” and ask “what if” are key to being an artist, engineer, scientist, or entrepreneur. I don’t know how to retain your sense of wonder or why some people lose theirs. I do know that letting children take things apart and tinker and explore on their own seems to help. Strangely, so does reading.

“There was a table laid with jellies and trifles, with a party hat beside each place, and a birthday cake with seven candles on it in the center of the table. The cake had a book drawn on it, in icing. My mother, who had organized the party, told me that the lady at the bakery said that they had never put a book on a birthday cake before, and that mostly for boys it was footballs or spaceships. I was their first book.”

I am pretty sure I had a rocket ship on my birthday cake but I read a lot of books growing up. I can still remember a line from Mr. Felling in my fifth grade English report card home: “Sean reads voluminously but only on one subject: science fiction.” It’s served me well although I have subsequently branched out to a much broader mix of subjects. I think science fiction, in exploring the impact of technology on both people’s lives and future society, was good preparation for both engineering and marketing. And if you don’t think entrepreneurs don’t appreciate science fiction–and the all too frequent fantasy–you need to read more business plans.

Childhood Friendship

“She was much older than me, at least eleven.”

The narrator remembers his first meeting with Lettie Hempstock when he was seven. Reading this reminded me of the big difference a few years make in childhood. The core of the story is his friendship with Lettie. She is more like an older sister, explaining how things work and looking out for him.

“I was not scared, though, and I could not have told you why I was not scared. I trusted Lettie, just as I had trusted her when we had gone in search of the flapping thing beneath the orange sky. I believed in her, and that meant I would come to no harm while I was with her. I knew it in a way that I knew that grass was green, the roses had sharp, woody thorns, that breakfast cereal was sweet.”

Mothers and Daughters, Fathers and Sons

“As we age we become our parents; live long enough and we see faces repeat in time. I remembered Mrs. Hempstock, Lettie’s mother, as a stout woman. This woman was stick-thin, and she looked delicate. She looked like her mother, like the woman I had known as Old Mrs. Hempstock.

Sometimes when I look in the mirror I see my father’s face, not my own, and I remember the way he would smile at himself, in mirrors, before he went out. “Looking good, ” he’d say to his reflection, approvingly. “Looking good.”

Although it’s not stated explicitly, I think the funeral at the opening of the book is for his father. And part of his reminiscing is about coming to a better understanding of his father’s life.

“I finally made friends with my father when I entered my twenties. We had so little in common when I was a boy, and I am certain I had been a disappointment to him. He did not ask for a child with a book, off in its own world. He wanted a son who did what he had done; swam and boxed and played rugby, and drove cars at speed with abandon and joy, but that was not what he wound up with.”

I remember a conversation with my father when I was seven or eight. We were on vacation in Colorado at a legal convention. I was excited about what I had just learned about atomic structure and was trying to explain something about electrons orbiting the nucleus of an atom. He said, “I am worried you are developing a closed mind. You only talk about things like the speed of sound or laser beams. You need to broaden your interests.” In hindsight, I think he was worried that these early interests did not bode well for a legal career, and in that respect, he was right.

I made a similar mistake with my daughter when she told me she wanted to be an artist at the age of eight. We were having lunch at Burger King, so I lifted her up to look in a small round porthole window in the door to the kitchen and said, “That’s where most of the artists work; make sure you really want it.” But we did buy her art supplies, and when my son told me the same thing a few years later, I skipped the speech and gave him books, pencils, and drawing pads.

Of course, I could get none of my children to read very many books, and never any that I had been interested in as a child. While I had been a swimmer and played pickup games of softball, they excelled in various organized sports–soccer, volleyball, and basketball. My grandchildren read more, so perhaps it alternates generations, or there is a genetic predisposition to independence. When my children were born, it became much clearer how much work my parents had done to care for me, and we became closer.

Give A Boy a Ball

When Lettie and the narrator first confront Skarthatch of the Keep, Lettie warns him to keep holding her hand for protection, and Skarhatch comes up with an ingenious way to make him let go.

She said, “Just keep holding my hand. Don’t let go. Whatever happens don’t let go.” […]

Now it seemed to have crouched lower to the ground, and it was examining us like an enormous canvas scientist looking at two white mice. Two very scared white mice, holding hands. […]

I thought it was smiling. Perhaps it was smiling, I felt as if it was examining me, taking me apart. As if it knew everything about me–things I did not even know about myself. […]

Something came hurtling at us from the center mass of flapping canvas. It was a little bigger than a football. At school, during games, mostly I dropped the things I was meant to catch, or closed my hand on them a moment too late, letting them hit me in the face or stomach. But this thing was coming straight at me and Lettie Hempstock, and I did not think, I only did.

I put both my hands out and caught the thing…and as I caught it in my hands I felt something hurt me, a stabbing pain in the sole of my foot, momentary and then gone, as if I had trodden on a pin.

Lettie knocked the thing I was holding out of my hands, and it fell to the ground, where it collapsed into itself. She grabbed my right hand, held it firmly once more.

It’s interesting that Skarthatch relies on “muscle memory” to trick the narrator into letting go. It reminds me of the scene in Huck Finn where he impersonates a girl but claps his legs together to catch a lump of lead and gives himself away. There is something about catching a ball that becomes a reflex.

I wonder how often we are undone by our habits and unconscious responses. Over time, I have learned that when I start to say, “Now don’t take this the wrong way,” it’s better not to say anything, that the habit of making a pre-apology is better replaced by keeping my mouth shut or finding another way to phrase the insight or suggestion that incorporates real empathy.

When the narrator later takes refuge in the fairy ring, the hunger birds cannot come up with as clever a way to get him to leave the protection of the ring. They appeal to his intellect and fears but cannot trigger another muscle memory reaction.

Portrait of the Artist as a Seven Year Old Boy

The last words of the hunger birds to the narrator before they depart foretell an unhappy future for him:

“How can you be happy in this world? You have a hole in your heart. You have a gateway inside you to lands beyond the world you know. They will call you, as you grow. There can never be a time when you forget them, when you are not, in your heart, questing after something you cannot have, something you cannot even properly imagine, the lack of which will spoil your sleep and your day and your life, until you close your eyes for the final time…”

Which may be he curse of all artists, to see worlds beyond the one we all know. The glimpse spoil their sleep and their life.

Related Blog Posts

This is also my Father’s Day post so I am including two sets of links, one related to the book, one to Father’s Day, and a quote by Neil Gaiman on the importance of finishing.

The Ocean at The End of The Lane

- John Clute on “The Ocean at the End of the Lane.”

The best review of the book that I have read, it details why Ursula Monkton’s prophecy to the narrator has come true. - TV Tropes “The Ocean at the End of the Lane“

- Tony Ortega “Is Neil Gaiman Exorcising His Past?“

- Goodreads “Quotes from The Ocean at the End of the Lane“

Father’s Day

- Kim Hubbard on a Family Reunion at Christmas

- Things I Have Learned From My Children

- Joseph Murphy (1925-2007) 7 Years On

- Mark Twain on Coming Home

- Father’s Day 2012

- Father’s Day 2011

- Uncle’s Day

- Lesser Sons of Greater Fathers

Neil Gaiman on Finishing

Quotes for Entrepreneurs–March 2014 contains three quotes by Gaiman, variations on a theme about the value of finishing.

“You have to finish things — that’s what you learn from, you learn by finishing things.”

Neil Gaiman

h/t Neil Gaiman’s Advice to Aspiring Writers

Gaiman has offered at least two variations on the importance of learning from finishing:

“Whatever it takes to finish things, finish. You will learn more from a glorious failure than you ever will from something you never finished.”

Neil Gaiman during “Question Time” section of “An evening of awesome with Hank and John Green” (Jan 15 2013) [transcript]

and

“Personally, I think you learn more from finishing things, from seeing them in print, wincing, and then figuring out what you did wrong, than you could ever do from eternally rewriting the same thing.”

Neil Gaiman in “No longer the blog without giraffes“

Pingback: SKMurphy, Inc. Giving Thanks - SKMurphy, Inc.

Pingback: SKMurphy, Inc. Father's Day 2011 - SKMurphy, Inc.

Pingback: SKMurphy, Inc. Father's Day 2012 - SKMurphy, Inc.

Pingback: SKMurphy, Inc. Whispers Under Ground, Broken Homes, Foxglove Summer

Pingback: SKMurphy, Inc. Quotes For Entrepreneurs-June 2015 - SKMurphy, Inc.