I have been working on my adjustments at the half for 2016 and thinking about lost arts and roads no longer taken. As much as we focus on creating and adopting new methods and technologies, it can be useful to consider capabilities that different societies have abandoned.

Roads No Longer Taken

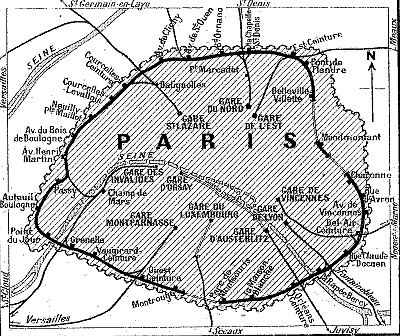

The picture is one of an abandoned railway in Paris called the or Petite Ceinture (“Little Belt”) that was built between 1852 and 1869 to transport goods but starting in 1862 it offered passenger service as well. It was a forerunner to “Le Metro” or Paris subway network.

In its approximate first eighty-years existence, the Petite Ceinture had a tremendous impact on the development of industry and Parisian districts that can still be seen to this day.

[Shown at right: The Petite Ceinture railway line of Paris in 1920, represented by a bold line]

In the middle of the Nineteenth Century, the booming railroads which radiated out of Paris needed to be connected for transporting goods. The growth of Paris needed goods yards in order to transport goods to the city that relied on raw materials and manufactured goods. The built of fortifications that encircled Paris in the 1840s, the « Fortifications de Thiers », needed in a strategic purpose the transport of troops along them. On 10 December 1851, just a few days after the coup of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, the future Napoleon III, the Petite Ceinture was created by decree for all these purposes.”

From the “History of the Petite Ceinture railway line of Paris” by the Society for the Preservation of the Petite Ceinture.

Initially built to support the military defense of Paris and to connect all of the railroads that came into Paris, it was replaced for the latter purpose in 1881 by the Chemin de fer de Grande Ceinture (the Great Belt Railway). It’s use for passenger service traffic ended in 1934 (except for one segment) but provided freight service and rolling stock exchanges for national trains until 1993.

I wonder if the original rail lines sliced up the property in a way that could not be easily re-purposed. I think there is a similar risk in Silicon Valley where our “cargo container” like buildings can be easily re-purposed like Lego blocks for other firms if the current owner or leaseholder moves out: the large arcology or spaceship structures of the Google and Apple headquarters may end up hard to sublet or salvage in a few decades when their current occupants no longer have any need for them.

Lost Arts of Piano and Brass in Lahore

The Dave Brubeck Quartet’s “Take Five” was a worldwide jazz hit, including places like Lahore, which in the 60s had a booming film industry. It was later nicknamed Lollywood in reference to other film industry regions like Hollywood, Tollywood, and Bollywood.

Welcome To Lollywood

A few decades back, Lahore had a booming film industry. Inevitably, it was known as Lollywood. “This was like a magic age that fell apart,” says Aqeel Anwar, a violinist in his 70s. He used to play in Lollywood soundtracks. “It was such an excellent time. I never thought it would end.”

For many years, South Asian movies kept Lahore’s session musicians pretty busy. And the Lollywood musicians were a class apart.

“In Punjab here in Pakistan, music is usually practiced by traditional musicians’ families,” says Mushtaq Soofi, a music producer. “They inherit it, they learn it from their parents and then transmit to the next generation.”

Things started to change in the late ’70s. General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq seized power in a coup, ushering in a period of religious conservatism in Pakistan that lingers to this day.

NPR: “A Millionaire Saves the Silenced Symphonies of Pakistan“

So, a change in government led to changes in popular entertainment and the incentives for learning to play music. Just as yeast is needed to make bread or beer, it’s difficult to master a musical instrument without a teacher who can coach you. Tacit knowledge is embedded in most industries and cannot easily be recovered from books, recordings, or videos.

Bringing Back The Music

Izzat Majeed made his money overseas, in finance. But he was born in Lahore in 1950, remembers Lollywood’s heyday and greatly admires its musicians. “It was a brotherhood of great musicians,” Majeed says. “I call them great because they are great and they lost it. They lost the avenue. They lost the money. They lost the creativity.”

Majeed decided to rekindle that creativity by building a new studio complex in Lahore — and reuniting these men to form the Sachal Studios Orchestra.

He teamed up with the music producer Mushtaq Soofi, an old friend. Soofi says he remembers the first day the musicians played together. “They were delighted and we were delighted, too,” Soofi says. “Because we thought the music was dead, but when we met them, we realized it’s not really dead.”

Izzat Majeed says he’s driven by a lifelong passion for music — especially traditional Pakistani music and jazz. “Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Brubeck, Quincy [Jones],” he says. “I can go on and on.” When he was 8, Majeed was taken by his dad to see Dave Brubeck perform in Lahore. Brubeck’s version of the classic “Take Five” seems to have made a big impression on the city.

“‘Take Five’ was a big hit in Lahore in the ’60s,” Majeed says. “Nobody knew what it was. It was just a melody and the whole thing. It was just a phenomenal, a fantastic piece of music.”

Majeed decided, a couple of years ago, that the orchestra should have a crack at “Take Five.” Its version has a South Asian twist. Majeed posted it online, and it went viral. Brubeck, who was still alive at the time, even sent a note saying how much he loved it.

NPR: “A Millionaire Saves the Silenced Symphonies of Pakistan“

It’s “Take Five” without piano and brass because those skills have been lost. Without a critical mass of talent it’s hard to jumpstart an industry. If the time is takes to acquire an expert skill is 10,000 hours of deliberate practice that acts as an “expertise acquisition speed of light barrier” for re-booting a lost art to an industrial scale.

“It’s not easy running an orchestra in Pakistan. Some skills do seem to have vanished, Majeed says. “I can’t find a single piano player in Lahore, maybe in Pakistan, a real piano player,” Majeed says. “People come and say, ‘Oh, I can play,’ but he can play atrociously–he doesn’t know what the piano, the real piano, is. There’s no brass left. Brass is dead.”

NPR: “A Millionaire Saves the Silenced Symphonies of Pakistan“

Last Man to Walk On The Moon

Last Man to Walk On The Moon

Gene Cernan was the last man to walk on the Moon; the year was 1972. I watched a documentary called “The Last Man on the Moon” about his journey and his life since, and am still not sure why we decided to shelve manned space exploration beyond orbiting the Earth in the 44 years since. The “Space Race” was initially driven by national pride and a fear of losing another kind of arms race.

Only 12 Men Have Walked on the Moon

- Neil Armstrong (Apollo 11)

- Buzz Aldrin (Apollo 11)

- Pete Conrad (Apollo 12)

- Alan Bean (Apollo 12)

- Alan Shepard (Apollo 14)

- Edgar Mitchell (LMP,Apollo 14)

- David Scott (CDR, Apollo 15)

- James Irwin (LMP, Apollo 15)

- John Young (CDR, Apollo 16)

- Charles Duke (LMP, Apollo 16)

- Eugene Cernan (CDR, Apollo 17)

- Harrison Schmitt (LMP, Apollo 17)

Perhaps when the Space Race returns it will trigger a new arms race. But much of the technology used to build autonomous drones will also find many uses in warfare so it’s not clear that an unmanned approach is doing less to foster a different kind of arms race.

The Moon is less hospitable than Antarctica so a colony there may be economically untenable; the same may true for long term missions in zero gravity: too many of our bodily functions may be so adapted to gravity that it may be like the loss of vital trace elements in our diet.

Conclusions

“One thing hastens into being, another hastens out of it. Even while a thing is in the act of coming into existence, some part of it has already ceased to be. Flux and change are forever renewing the fabric of the universe, just as the ceaseless sweep of time is forever renewing the face of the eternity. In such a running river, where there is no firm foothold, what is there for a man to value among all the many things that are racing past him?”

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations Book 6 Section 15, translated by Maxwell Staniforth

The abandonment of a technology or the loss of an art or a method is the flip side of the adoption of new technologies and methods. A trickier challenge is when techniques for scaffolding or bootstrapping that don’t appear in the finished article are lost. We can reverse engineer Roman concrete because samples still exist, but we can only speculate about Greek fire. I spend most of my efforts trying to obsolete existing tools and practices. But to be effective, I must understand what I am asking people to give up.

“Anything ridiculous on the surface may have all the more value to it underneath. I have a rule. When I see something that makes absolutely no sense whatever, I figure there must be a damn good reason for it.”

Peter DeVries in “Let Me Count The Ways”

Related Blog Posts

- Kenopsia: Bare Ruined Choirs Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang

- Gary Smith on Bebop As a Model For Innovation The right kind of competition in a constricted geography fosters rapid innovation.

- Information That’s Not Written Down

- Knowledge That Is Not Written Down, Yet

- Observing, Orienting, Doing Homework, and Paying Dues

Opening Photo Credit: Petite Ceinture by “Naughty Little Croissant” used with attribution.

Pingback: Silicon Valley July/August 2016 Roundup

Pingback: SKMurphy, Inc. Quotes for Entrepreneurs-July 2016 - SKMurphy, Inc.

Pingback: SKMurphy, Inc. A Childhood Memory or Two - SKMurphy, Inc.

Pingback: Marcelo Rinesi: The Expertise Light Speed Barrier - SKMurphy, Inc.

Pingback: Video & Slides from "Limits of I'll Know It When I See It" Talk at SFBay ACM - SKMurphy, Inc.