Here are seven sets of insights from “Organize for Complexity” by Niels Pflaeging that I found useful for entrepreneurs who scaling their startup and intrapreneurs who are driving change in large organizations.

7 Sets of Insights from “Organize for Complexity” by Niels Pflaeging

In “Organize for Complexity” Niels Pflaeging offers a number of observations and insights on the challenges that organizations face in managing complexity. I found it thought provoking although I disagreed with a few of the points he made, in particular that “innovation is always carried out in the center, away from customer contact.” Because he offers no examples or case studies it’s very possible I have completely misunderstood what he is trying to say. He does offer two base definitions that I find useful:

In “Organize for Complexity” Niels Pflaeging offers a number of observations and insights on the challenges that organizations face in managing complexity. I found it thought provoking although I disagreed with a few of the points he made, in particular that “innovation is always carried out in the center, away from customer contact.” Because he offers no examples or case studies it’s very possible I have completely misunderstood what he is trying to say. He does offer two base definitions that I find useful:

- Complicated systems operate in standardized ways, they are composed of non-ambiguous cause and effect chains that are predictable and controllable.

- Complex systems have the presence or participation of living creatures and as a result produce surprises.

In what follows I have culled 7 sets of insights that resonated with my experience as applicable to startups.

Key Questions

- How can we adjust a growing organization without falling into bureaucracy?

- How can my organization deal with growing complexity?

- How can we become more capable of adapting to new circumstances?

- How can we overcome existing barriers to performance, innovation, and growth?

- How can my firm achieve higher engagement and become an organization more fit to human beings overall?

- How can we produce profound change, without hitting a wall?

These are excellent questions and one that most startups start to face once they have more than a dozen employees. Obviously, complexity increases as headcount and scope of operations increase.

Symptoms or problems: not everything that looks like a problem is one.

“Symptoms are the visible effects of a problem: e.g. defects, mistakes, bugs, unpunctuality, and resistance against change. The attempt to find solutions for symptoms alone, or tinker with before the problem has been understood, breeds failure and makes learning impossible.”

When I worked in Marketing at VLSI Technology meetings would never start on time. It was something I had never encountered before. A meeting would be called, a few of us would show up and we didn’t have a quorum. People would wander in hoping the meeting had started and then leave again when it hadn’t to make one more phone call or send one more email. A new VP was hired and when in his first meeting started 20 minutes late and it was clear that this was business as usual he let everyone know that going forward there would be a $5 fine if you were 5 minutes late and a $1 for each additional minute. Meetings started promptly, which saved everyone time.

Later when I worked at Cisco a new VP of Engineering was hired and in response to persistent complaints about software quality he decreed that for the next three months we would implement no new features we would only fix bugs. Three months stretched to six and it was a disaster. Many bugs were a symptom of a need for architecture improvements, but that sounded too much like adding features. We were too busy mopping the floor to turn off the faucets. More fundamentally it was a conceptualization of software defects as something unwanted that could be removed–like a small child might pick raisins out of their morning oatmeal because they don’t like their taste and be left with an acceptable breakfast.

Two different situations, two incoming VP’s attacking a symptom to establish their authority. One had an immediate positive outcome and while the second had some positive benefits but did a lot of harm. The first was a bounded intervention that the VP could monitor directly, the second was much more wide ranging and therefore harder to observe. What we actually needed was better configuration management and a progressive feature freeze that allowed key architectural improvement and major enhancements to be shepherded through in parallel with a number of ongoing bug fixes. That took another two years or so.

Data, Information, Knowledge, and Mastery

- Information is data in a context: the data, contextualization, and information can be stored independent of anyone.

- Knowledge is a held by people and teams and can be applied to known problems by those who have learned skills or developed expertise.

- Mastery is a human capability to solve new problems. It can only be developed through disciplined practice which creates new knowledge.

Niels Pflaeging in “Organize for Complexity“

I agree with this formulation that data and information or properties of computing systems while knowledge and mastery are held by people. There is always value in checklists and written procedures that can guide action and help newcomers orient, and in software what provides automated checking and verification, but creative improvisation and innovation requires human insight in the context of a complex system.

Making Use of Social Process (Social Pressure)

- Let people identify with a small group.

- Give them shared responsibility for shared goals.

- Make all information open and transparent to the team.

- Make performance information comparable across teams.

Ultimately organizing for complexity is about empowering teams, not about empowering individuals.

Niels Pflaeging in “Organize for Complexity“

I am split on this one, you have to give everyone a certain amount of autonomy to experiment and tinker, but the team is the natural place to analyze trade-offs and agree on a course of action that requires insight and review by different experts.

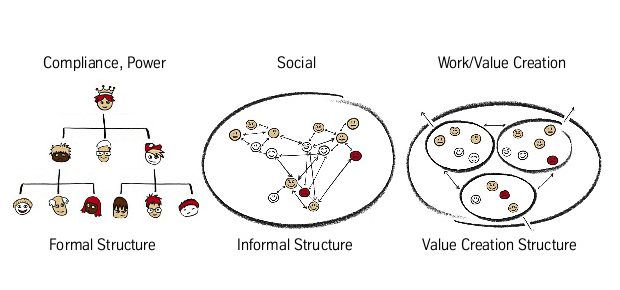

Organizations Have Three Interacting Interlocking Structures

Image from slide 34 of “Organize for Complexity – Keynote by Niels Pflaeging at HR Congres (Malaga/ES)”

- Formal Reporting Hierarchy: manages formal budget and compliance with laws and regulations.

- Informal Networks: hold social capital and operate in the “white space.”

- Expertise Networks: hold intellectual capital and procedural knowledge that enables value creation.

Niels Pflaeging in “Organize for Complexity“

The formal hierarchy can control value creation where knowledge or mastery is not a factor, or at least not a major factor. In a startup, the founders are initially at the top of the formal reporting hierarchy and at the center of expertise networks. But as the firm grows and more experts are hired, in particular when new kinds of expertise become essential to success, you then see a richer set of expertise networks with less overlap over the formal reporting hierarchy. Founders that cannot hire experts more knowledgeable than they are often find themselves masters of a stalled or self-limited business.

Promote Self-Development and Mastery

| Formal Methods vs. Integrated Learning | ||

|---|---|---|

| We Overrate | We Underrate | |

| talent | systematic disciplined learning | |

| classroom training | learning integrated into work life | |

| formal instruction | inspirational interaction, informal network, communities of practice | |

I think this is actually reversed for early stage startups with respect to classroom training or formal instruction: the founders and early employees tend to be flexible generalists who are fast learners. As the firm grows they come the appreciate the need to balance informal and ad hoc methods that tend to be “on the job” with a certain amount of formal training that can be useful for new employees and new managers.

Odds and Ends

- New behaviors and skills need to be practiced with discipline to deepen them.

- Recruiting and promotion are key business decisions that are highly time-consuming.

- Individual mastery is the only viable problem solving mechanism in complexity.

- Resistance to change is natural and guided by self-interest and/or fear and uncertainty about the future.

Niels Pflaeging in “Organize for Complexity“

I think mastery is also possible at a team level after a team has had a chance to collaborate on a number of projects and is not to be cast aside lightly. Rotation and reorganization of teams has other benefits–for example cross-fertilization of effective practices and strengthening of informal networks–but keeping effective teams together enables much more effective problem solving and value creation.

I think “resistance to change” is much more about resistance to loss–or the possibility of loss bundled into the uncertainties of the actual effect of a chance–as well as reasonable expectation of unexpected negative consequences. Effective change agents are alert to the possibility of breaking what’s working and allow for experimentation and negotiation of partial or modified implementations to achieve better shared outcomes. If you are simply “rolling out” a change then you are engaged in a forced migration that may abandon as much value as it is intended to foster–sometimes unanticipated and unintended consequences can far outweigh any benefit.

Pingback: Cultivate Formal Controls, Informal Collaboration, and Value Creation Networks