My longer answer to “Do you ever get the feeling that everything you know is wrong?” The short answer is “yes, every few years.”

Do You Ever Get the Feeling That Everything You Know is Wrong?

I worked in Semiconductors in the 1980s (CAD startups, AMD/MMI) and networking in the 90s (3Com, Cisco) taking 1994-98 to get involved in a number of web startups and then striking on out on my own with SKMurphy in 2003 until now.

I worked in Semiconductors in the 1980s (CAD startups, AMD/MMI) and networking in the 90s (3Com, Cisco) taking 1994-98 to get involved in a number of web startups and then striking on out on my own with SKMurphy in 2003 until now.

The semiconductor industry was on a four-year business cycle; at MMI, we were on five days of work for four days of pay for 18 months between 1984 and 1987, which worked really well in practice. I didn’t think so at the time, but then we went through layoffs and a merger, and I saw how completely arbitrary decisions were about how to keep and who to let go. I was a supervisor in a group, and my manager decided to let go of two of the newer hires, who were less productive, but watching other groups, they were head and shoulders above many.

It was also a period of tremendous change in semiconductors in that we were moving from essentially manual methods for designing and verifying chips. Cutting rubylith was giving way to CALMA and then to automated layout (place and route tools). Checking for errors by visual inspection of a plot on a light table with a magnifying eyepiece gave way to a rich variety of automated verification tools.

So I had witnessed two kinds of upheaval: older manual skills being obsoleted by software and fluctuating economic performance where we were incredibly optimistic one quarter and then living with a 20% pay cut for more than a year shortly thereafter. The same thing happened again in the dotcom era.

Early Web 1993-4

in 1994 there might have been a few hundred websites in the world and for the most part if you were not in a technology job you didn’t use email.

Then the web became a brochure and then a fabric for commerce and other more complex workflows.

I can remember in 1994 talking to someone who had started a software consulting company and suggesting that he get a website and put the URL on it–which he interpreted as being about as useful as including a benediction in Iroquois. Besides, he had already printed his stationary, which cost several hundred dollars! I started writing a column called “Nickel Tours of the Net” in 1994 in EE Times, where I would review websites in what was then a print-only weekly magazine. When they went online shortly thereafter, it was quite tricky to work out the conventions to be able to publish a print version with footnotes for the URLs and an HTML version.

Dotcom Exuberance

In the next six years or so, there was a substantial upheaval in business practice and a lot of foolishness as investment money flowed in that did not recognize where the puck would end up. By 2000, there was a sense for established businesses that “everything you know is wrong.” Now, what made sense was to take an entire VC round and buy a Super Bowl ad to sell Pet food online. I remember attending a presentation by FogDog Sports in January of 2000 at an entrepreneur event with at least 200 people in attendance. They outlined their strategy, and a young MBA type got up and asked, “I didn’t hear in your presentation what your sustainable competitive advantage was?”

The speaker was contemptuous of the question, answering, “Those rules are so over. That’s last century thinking.” The room erupted in laughter. The same question had occurred to me, and I was glad I had not asked it; it must have felt terrible to have 200 people laughing at you. Within six months, FogDog was at about 10% of the IPO high, and it was starting to become clear that the new rules might be getting rolled back. The 9-11 attack ended most remaining optimism, and we became much more prudent for a while.

9-11: Watching People Jump Off the Twin Towers

The morning of 9-11 was completely disorienting: watching the first tower collapse seemed like a special effect. When the second one went, I had the strong sensation I was a minor character in a Tom Clancy novel. A number of us gathered in a training room that was not being used so that we could watch a working TV. It was working to the extent it could get a Spanish channel, but only a Spanish channel for reasons that none of us could figure out. The most chilling scenes that they played over and over but which I did not see on any network or US cable channels when I got home were those of people jumping off of the towers before they collapsed. I was reminded of an old movie, “The Towering Inferno,” and I kept thinking there must be a way to put that fire out or get those people off the roof. But no happy Hollywood was ending to be found.

Challenge is to Separate Transients from Real Transformations

To me the key thing to try and distinguish is between transient phenomena and real transformation. It’s harder than it looks. If you were trying to navigated a long distance by sailing you would like to know

- the location of islands, continents, and other land masses that change very slowly if at all

- prevailing currents (likely but also subject to seasons)

- prevailing winds (likely but also subject to seasons)

- what season

- how to navigate by day and at night

Related Blog Posts

- Thomas Schelling on Strategic Surprise

- Organizing Your Experiment Log

- The Illusion of Progress

- Some Unsolicited Advice from David Cain

- Illusion of Omnicompetence: Smart and Competent are Domain Specific

- Remembering 9-11: Our Children Will Also Live in Interesting Times

- Cultivating Calmness in a Crisis

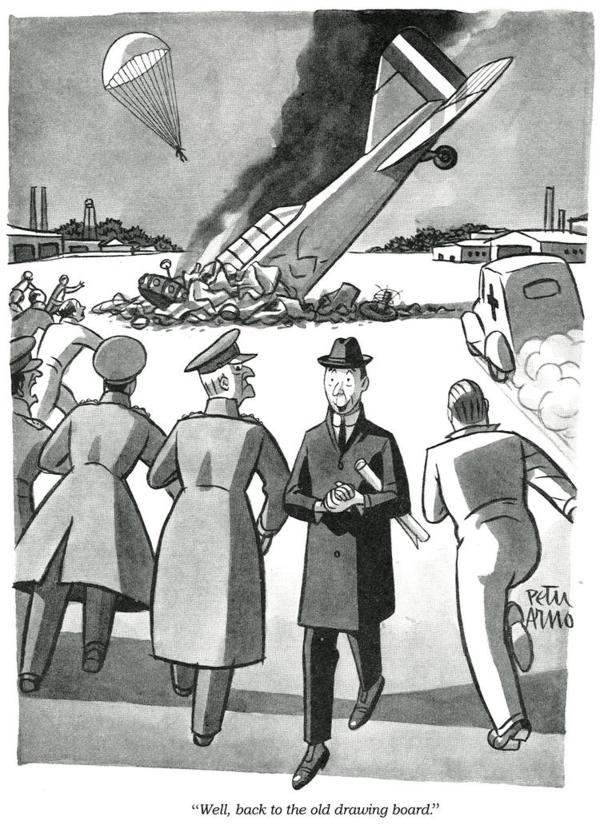

Image Credit: Peter Arno‘s famous 1941 New Yorker Cartoon: “Well, back to the old drawing board.” (h/t “Comic Book Legends Revealed #221“)

a great article, thanks for sharing

Pingback: SKMurphy Perspective Counterbalances Excess Pessimism or Optimism