Video and an edited transcript from the “Make Something that People Want”” briefing by John Nash at the Aug-24-2022 Lean Culture meetup.

John Nash on “Make Something that People Want”

At its core, building a business is simple:

- Make something that people want

- Get it in front of those people

- Charge enough money to make a profit

In the video below, John Nash shares his experience making this happen and how to go about making something that people want. Although the basics are quite straightforward, John shares with the group some practical tips that he has picked up-–as well as a few painful mistakes he made along the way. John Nash’s lessons draw from design thinking, value proposition design, prototyping and the jobs to be done model.

About John Nash

John Nash (@JNash) is a professor and design thinker who helps improve outcomes, expand impact, and increase happiness. He works with teams from Silicon Valley to the Silicon Prairie and in countries all over Europe and Asia.

John brings considerable direct experience as an entrepreneur to his efforts–as he says, “I am in the less well populated category of professors who have been entrepreneurs who have actually made payroll.” He helps entrepreneurs to engage with customers in conversation and by direct observation of current practices, leveraging prototypes to unlock their view of their needs and constraints on potential solutions, and careful consideration of what is needed for a compelling value proposition.

John founded the Laboratory on Design Thinking at the University of Kentucky.

Key Takeaways from Make Something People Want

Below are some of our favorite takeaways from the talk.

Jonathan Greechan’s Rule of One

In the short video snippet below, John Nash shares the Rule of One popularized by Jonathan Greechan, co-founder of the Founder Institute. It’s that entrepreneurs should start by solving one problem, for one customer, with one product, that has one killer feature, and one revenue stream.

Pixar in a Box

Stories let us share information in a way that creates an emotional connection to your product. Stories help us to understand the information, and it makes our product memorable. Because stories create an emotional connection, we can gain a deeper understanding.

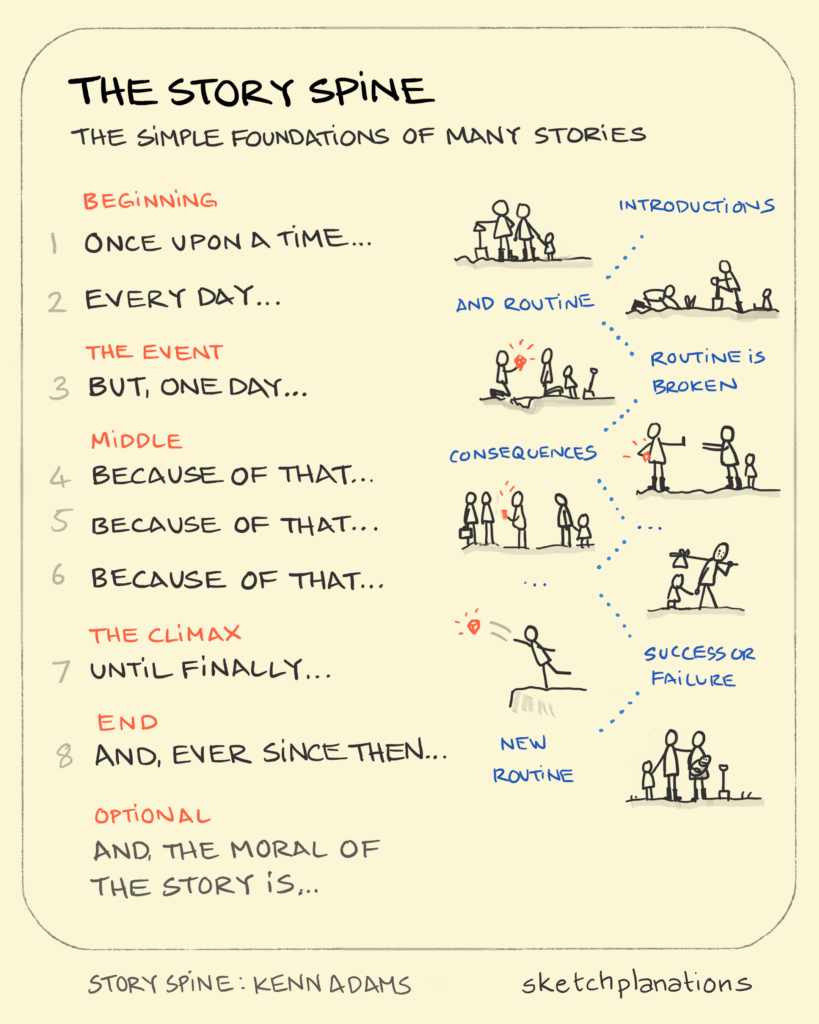

In the video below, John explains a great little resource for developing your story is Khan Academy’s Pixar in a Box with some lessons on how to use a story spine to tell a product story in eight steps.

- Once upon a time, a person was in a problem situation.

- And every day, these terrible things were happening to them.

- Until, one day, your product arrives.

- Because of that, a good thing happens.

- Because of the first good thing, a second good thing happens.

- Because of the second good thing, a third good thing happens.

- Until finally, an amazing outcome occurs.

- Ever since then, this is what they have experienced.

Using these eight steps and sketching out a little storyboard, you can show that to partners, to users, to customers, and they can react to saying they can either see them. The beautiful thing about a storyboard or any story is that, or a good prototype is that the user can see themselves in the experience. And when they can see themselves inside your experience, then you’re able to get insights as to whether or not you’re on the right track or not.

Case Study: Make Something People Want

John Nash’s Book Recommendations

Book recommendations include:

- Bob Moesta, “Demand-Side Sales”

- Indi Young, “Time to Listen” and “Mental Models“

- Alex Osterwalder et al, “Value Proposition Design“

- Abbie Covert, “How to Make Sense of Any Mess“

- John Warrillow, “Built to Sell“

- Kindra Hall, “Stories that Stick“

- Austin Kleon, “Show Your Work“

- Jim Ross, “Excuses, Excuses! Why Companies Don’t Conduct User Research“

- Rob Fitzpatrick, “The Mom Test”

- Clayton Christensen, “Competing Against Luck”

- Ash Maurya, “Running Lean “

Tools and Ideas

- Pixar in a Box The Story Spine – A technique for creating a storyboard prototype

- Maze.co – Solutions for user insights

- Jonathan Greechan‘s (@JonnyStartup) Rule of One.

Full recording of Make Something People Want

Edited transcript from Make Something People Want

The following transcript has been condensed and edited for clarity; hyperlinks have been added for context.

Sean Murphy: Welcome to the August 24th webinar for a combined session of the Lean Startup Circle in Silicon Valley and the Lean Culture Meetup. My name is Sean Murphy, and I’ll be the host for today. Our speaker is John Nash.

John Nash is a professor and design thinker. He helps teams improve product outcomes and expand their impact. He works with teams from Silicon Valley to Silicon Prairie and countries all over Europe and Asia. John brings considerable direct experience as an entrepreneur to his efforts. He told me, “I’m in the less well-populated category of professors who’ve been entrepreneurs who’ve actually had to make payroll.” He helps entrepreneurs engage with customers in conversation and by directly observing their current practices. He sees prototypes as a valuable way to unlock customer understanding of their needs and constraints on potential solutions. John founded the Laboratory on Design Thinking at the University of Kentucky.

John Nash: It’s great to be here, Sean. Thanks for that introduction. You mentioned the importance of prototyping, and I want to explore that. In particular, how can entrepreneurs test their ideas to understand their market better? I want to share some examples where entrepreneurs avoided–or at least escaped–the trap of making things they thought customers wanted when customers had little or no genuine interest.

Justin Kan: from Kiko Calendar to Justin.tv to Twitch

John Nash: Justin Kan says he started out to make a calendar app called Kiko Calendar to compete with all the other calendar apps out there. The team programmed something they thought would be interesting to do, but they never talked to anybody. It failed and the code was sold to Tucows. The team moved on to Justin.tv, which he admitted was something else that probably no one wanted. Customers told them, “What you’re putting out there on the Internet is really boring, but I would like to create my own live video stream. So how do I do that?”

They listened and decided, “Well, we’ll make that happen.” They noticed that customers were publishing a new kind of content on their platform, the live streaming of video games.

So, instead of letting that pass, Justin and his team went out and talked to gamers. They learned that the gamers wanted something that they had not heard of before on their platform. The gamers wanted to get paid for being able to follow their passion and create video game content. So, they took that idea and ran with it, ultimately creating Twitch.

So the moral of the story is: if you want to make something people want you must talk to them up front. And you should consider how you will explore and validate what they are telling you.

Don’t Shoot for the Moon, Aim for a Niche

John Nash: I have noticed that entrepreneurs sometimes have to “go big or go home” or “shoot for the Moon.” So they worry that focusing on a niche will prevent them from getting big. But Jonathan Greechan, the co-founder of the Founder Institute, has a Rule of One for entrepreneurs when they are starting out that says just the opposite.

“Entrepreneurs should start by solving one problem, for one customer, with one product, that has one killer feature, and one revenue stream.” Jonathan Greechan,

When you start to think about things this way, you focus and niche down. Many entrepreneurs resist this because they worry they won’t get to a large market. But this rule gets you to a place where you can gain a foothold; once you have that, you can start to think about how to scale from there.

Prospects Have Trouble Grasping My Product’s Utility

John Nash: My mantra lately has been “make things people want. I wonder what people’s experiences have been thus far in trying to test their ideas. It’s critical to think about how to talk to your customer. And how to reach out to people in your orbit that you might be selling to so that you can find out what they need and make something they want.

Attendee A: I am working on a couple of projects. I have read the The Mom Test by Rob Fitzpatrick and I’m still working out how to ask proper questions.

Attendee B: I am in the AI/ML space and my MVP is a model. But when I show it to people they have trouble grasping the utility because it’s more of a conceptual solution. They have trouble determining who in their organization could use it.

John Nash: If you have a clear picture of the benefit or outcome from the service, then one thing we’ve done is to give people a picture using story boards. You don’t have to go very technical, focus on the result that they want.

Most people try to buy progress when they struggle toward an outcome they want. So to the extent that your service or your product can help people make progress, you can portray that in a story or a storyboard. One good book on this is by Bob Moesta called “Demand-Side Sales”

Sean Murphy: One way we help clients explain the benefits of their product is to write a synthetic case study that says, “Here’s an example of what someone else has achieved.” A case study allows you to explain the process from the customer’s point of view and an example outcome. This case study can be in the form of a blog post, a press release, diagrams, or a short video. Whatever forces you to explain what they need to do and the outcome you can deliver. Customers are actually paying for the result. When John says, “Make something people want,” it’s not your product that they want. It’s the result your product has on their business or life.

How Do You Prototype a Service?

Attendee C: How can you apply this to service?

John Nash: I get asked this a lot. It’s hard because services can feel a little mushy or somewhat amorphous. People experience services more than they actually use them.

I’m a big fan of paper prototyping. I teach a class on design thinking at the University of Kentucky. And one of the things we always start with is some version of the Wallet Project, an iconic design thinking exercise developed at the D school at Stanford. My students have little or no design experience, but I ask them to draw their ideas. Many people dislike drawing and depicting their ideas visually. I insist they draw, but tell them it doesn’t have to be incredibly fancy; it can be stick figures and circles and Xs and arrows.

I give them five minutes to make five drawings. What happens next is fascinating: these incredibly rudimentary drawings provide rich starting points for conversations about what’s going on in the solution. The designer and their target user discuss the sketches. Both point to various parts of a sketch, asking questions about what it means. The drawings create a conversation much richer than a memo or text write-up. One reason paper prototypes for apps work so well is that you can slap down a fake screen, ask people to point at what they’ll do, and then show them the next screen. It creates interaction and creative collaboration.

Sean Murphy: Your teaching paradigm reminds me of John Gall’s observed that “successful complex systems evolve from successful simple systems. I think a sketch or hand drawn diagram also forces you to think about having a conversation with the customer about needs. It acts as a “sacrificial concept” that you don’t risk becoming too attached to but that advances the conversation.

How Do You Avoid Fooling Yourself?

Attendee D: It’s been my experience that it’s impossible to know if you’re doing proper validation. I have convinced myself that I have all of the proper data and signals from the proper customers, but the product finds a few customers and stalls. Of course, luck is always a factor, but the only strategy I have come up with is to hold two opposing opinions in my mind at the same time. I have tried to do this by seeking out some real haters–not people trying to offer constructive criticism or coaches but people who hate the idea– and not be hurt by what they say. But it requires so much strength that I am not good at it yet.

John Nash: I really appreciate your question, and I thank you for sharing it. Your approach sounds similar to what we ask our students and the people that we work with to do. I call it “design at the edges.” You select from a continuum of users. You must avoid getting trapped in the middle and talk to “haters” and people who love the idea. We know that if we only talk to people who love the idea, we may overlook some flaws, but there is a similar risk if you only add people from the middle. But if you work with the haters and design there, you will be where you can start getting helpful feedback.

David Kelley says that prototypes should embed “strong opinions weakly held. They should have a point of view. But just as von Moltke said that “No battle plan ever survives contact with the enemy,” no prototype survives first contact with a user. So feedback should be your goal. Don’t take it personally. You have to seek people who will rip it apart.

Sean Murphy: I think the lukewarm response is deadly when someone says, “That’s nice.” Another dead end is when you hear, “it’s not really a problem for me.” You are not going to be able to gather evidence that will lead to valuable insights.

Taking Advantage of Pixar’s Story Spine

John Nash: I think entrepreneurs should challenge themselves to tell a compelling short story about the impact of the product. I like this great–but simple–technique that Pixar developed. There’s a small corner of the Khan Academy called Pixar in a Box that offers lessons on how to use the Pixar Story Spine. This is an eight-step methodology for crafting a storyboard that goes from problem to solution and outcome. It goes like this:

John Nash: I think entrepreneurs should challenge themselves to tell a compelling short story about the impact of the product. I like this great–but simple–technique that Pixar developed. There’s a small corner of the Khan Academy called Pixar in a Box that offers lessons on how to use the Pixar Story Spine. This is an eight-step methodology for crafting a storyboard that goes from problem to solution and outcome. It goes like this:

- Once upon a time, a person was in a problem situation.

- And every day, these terrible things were happening to them.

- Until, one day, your product arrives.

- Because of that, a good thing happens.

- Because of the first good thing, a second good thing happens.

- Because of the second good thing, a third good thing happens.

- Until finally, an amazing outcome occurs.

- Ever since then, this is what they have experienced.

Use these eight steps to sketch out a simple storyboard that you can show to partners, users, and customers. Then, they can react and tell you what they see in them. The beautiful thing about a storyboard–or any story–is that it’s a good prototype for the user experience. Based on their reactions and feedback, you can get insights as to whether or not you’re on the right track.

We combine this with a jobs-to-be-done approach where you don’t focus on your product. Instead, you explore the struggle in steps one and two and unpack why it’s hard for them to make the progress they want. The quirky thing about starting with the struggle is that it sets aside traditional notions of competition.

Clayton Christensen calls this “Competing Against Luck” because people’s reasons for a particular choice depend upon a host of factors that often have nothing to do with your competitors. When you focus on the pain of their current situation and what’s blocking them from making progress, you will get a much better sense of their needs.

How Can I Take Advantage of Laboratory on Design Thinking?

Attendee E: Do I need to enroll in the University of Kentucky to take advantage of the Laboratory on Design Thinking?

John Nash: No. We have a pretty egalitarian view on participation. The course I have been describing is for students at the University of Kentucky. But my partners and I do a lot of community work. We work with outside agencies, and we also do research. Our outreach includes courses and workshops where we help groups think through how they can apply jobs-to-be-done and design thinking principles. Reach out on the contact page for the Design Thinking Laboratory

When Should You Use Surveys?

John Nash: I lean slightly toward qualitative research because I think that’s the place where you get the most interesting insights. Of course, there’s still a place for surveys, but I think the quantitative data they provide is more useful in later phases of the design cycle.

We typically start with interviews, get some ideas for prototypes and start sharing them with users. We want people to use and interact with our prototypes, whether they are drawings, storyboards, or mockups. We love it when people misuse our prototypes because that tells us where we made a wrong turn or may need to add a feature.

I’m not a big fan of using surveys at the front end because they tend to block the follow-up you need. I also teach survey design, and one of the caveats that I give students is that you can know the answer a particular user selected, but you don’t know why. Understanding user motivation is critical to crafting useful features.

How To Manage A Negative Reaction To Your Product Idea?

Attendee F: How do you tell if someone critical of your idea is being negative just to be a hater or they are being realistic? How do you tell if critical feedback is from someone who is trying to help.

John Nash: Great question! I love that. I took a creativity workshop from Bernie Roth at Stanford almost 20 years ago: one thing he covered was how to take feedback. Always say “Thank You.” Because when we were showing the prototypes and getting feedback, we were not supposed to defend our ideas or coach users on where they should go with the prototype.

How can you tell if they are being a crank or offering valuable feedback? I don’t have a perfect test. I think you have to start with your intuition. You have to compare the feedback with what else you have heard. Is it consistent? If you have to talk to enough people, which can often be five or six, you can tell if this person’s on the right track or if they’re just being unkind.

Sean Murphy: You don’t need everyone to like it, just enough to show that you have found a niche you can start in.

I would say one thing about “intuition.” I work with many scientists and engineers. They are often blessed with remarkable intuitions about the physical properties of matter or how to organize software architectures. But people’s emotions can be a mystery. So when you say things like, “You’ll just be able to tell,” they may not have that same level of intuition about people’s motivations as they would about a physical property.

I like your suggestion of looking for consistency with other feedback. The other thing I try to determine is the prospect’s view of the task they are trying to accomplish. I can take a lot of specific criticism that flows from, “Here’s the job I’m trying to get done.”

Bill Seitz: I wanted to share my perspective as a product manager. If you do 15 different interviews and you have one person that hates your product, that’s very different than if five people hate it. So you have to look at the fraction of haters in the complete interview set. If you have too many, it can be a sign that you are doing something wrong with the product or solving the wrong problem for some people. Or you may be defining your segment too broadly, which means you will have problems with targeting and the cost of sales or customer acquisition.

If the five hate it for the same reason, that’s a separate case from the five hating it for different reasons. You are looking for patterns and reviewing your assumptions: is there a mindset or set of needs you did not consider? If a group has to work together and adopt at the same time, that’s a different context from one individual at a time, and it can be much more challenging.

John Nash: If you have enough haters who have a common complaint there might be an opportunity for a new product.

That’s a Wrap

Sean Murphy: Well, John, we’ve had a lot of interest and a lot of excitement. I really want to thank you for what’s been an extremely informative session.

John Nash: I’m grateful to have the opportunity to talk with folks. It’s good to be reconnected back in the Valley. And if I can be of any support to the work that anybody is doing, please reach out.

Related Blog Posts

- A Holistic Approach to Launching a Bootstrapped Startup

- Narrative Rationality: Be Mindful Of Your Self-Description

- A Beta Customer is Not a Tester or a User But an Early Customer

- Concierge MVP or Service-First Forces You To Be Your Own Test Pilot

- Sketching the Likeness of an Imaginary Business

- Planning in a Bootstrapped Startup: a Model from Will Kamishlian

Answers the question: “how do you plan when no plan survives contact with the market?” - For New Products Prospect Objections Are Valuable Data

- Mark Brinkerhoff: Starting With a Sketch Saves Money

- 40 Tips for B2B Customer Development Interviews

- Founder Story: John Nash, CEO Color Vision Store

Image Credit: “Story Spine” by Jonah Hey, used with attribution.