Some thoughts from Marshall McLuhan and others on how to see the future when the past, spread out before us, is all we see.

Marshall McLuhan: How To See The Future

“To be a futurist, in pursuit of improving reality, is not to have your face continually turned upstream, waiting for the future to come. To improve reality is to see clearly where you are, and then wonder how to make that better.”

Warren Ellis “How To See The Future” (Sep-7-2012)

I think this is a good start on seeing what’s coming now. Robert Lucky observed, “I have gradually come to appreciate that the really important predictions are about the present. What is happening right now, and what is its significance?” It’s hard to make sense of today because our mental models lag. History is often a good guide when it comes to people and cultural issues. But technology remains relentlessly surprising, especially the interaction between two or three seemingly unrelated developments: take a steam engine that generates a circular motion to pump water out of a mine and put it on wheels and now you have a locomotive and railroad. It was hard to foresee that locomotives would soon outrun horses, pull much more than teams of horses, and travel much farther before needing to refuel than a horse-drawn wagon.

I think this is a good start on seeing what’s coming now. Robert Lucky observed, “I have gradually come to appreciate that the really important predictions are about the present. What is happening right now, and what is its significance?” It’s hard to make sense of today because our mental models lag. History is often a good guide when it comes to people and cultural issues. But technology remains relentlessly surprising, especially the interaction between two or three seemingly unrelated developments: take a steam engine that generates a circular motion to pump water out of a mine and put it on wheels and now you have a locomotive and railroad. It was hard to foresee that locomotives would soon outrun horses, pull much more than teams of horses, and travel much farther before needing to refuel than a horse-drawn wagon.

More significant were the secondary effects. It can be hard to foresee the impact of just a doubling. If you can haul goods twice as far in the same amount of time, you can serve a four times larger market (since the area is now four times larger). The economic value of a market tends to increase as the potential for interactions between buyers and sellers, if you double both, you end up with roughly four times the economic value. If the speed and distance covered by the locomotive increase the number of buyers and sellers by a factor of four, you end up with sixteen times the economic value, a counter-intuitive result.

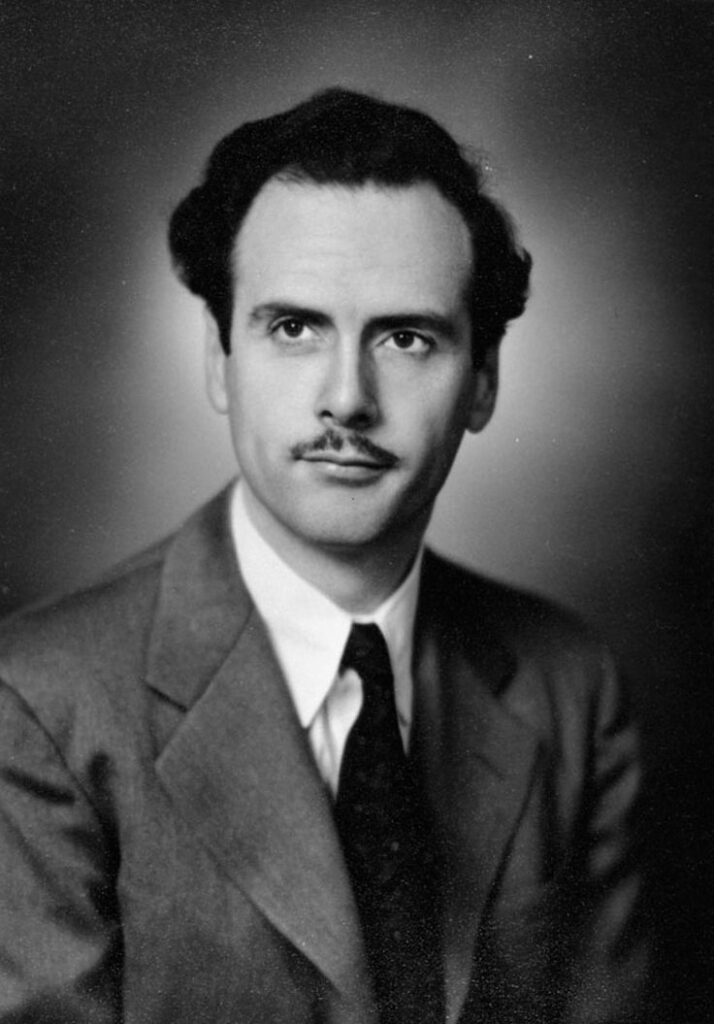

Marshall McLuhan on Our Rear-View Mirror View of World

Eric Norden: Why should it be the artist rather than the scientist who perceives these relationships and foresees these trends?

Marshall McLuhan: Because inherent in the artist’s creative inspiration is the process of subliminally sniffing out environmental change. […]

Norden: Is the public, then, at last beginning to perceive the “invisible” contours of these new technological environments

McLuhan: People are beginning to understand the nature of their new technology, but not yet nearly enough of them — and not nearly well enough. Most people, as I indicated, still cling to what I call the rearview-mirror view of their world. By this I mean to say that because of the invisibility of any environment during the period of its innovation, man is only consciously aware of the environment that has preceded it; in other words, an environment becomes fully visible only when it has been superseded by a new environment; thus we are always one step behind in our view of the world. Because we are benumbed by any new technology — which in turn creates a totally new environment — we tend to make the old environment more visible; we do so by turning it into an art form and by attaching ourselves to the objects and atmosphere that characterized it, just as we’ve done with jazz, and as we’re now doing with the garbage of the mechanical environment via pop art.

The present is always invisible because it’s environmental and saturates the whole field of attention so overwhelmingly; thus everyone but the artist, the man of integral awareness, is alive in an earlier day. In the midst of the electronic age of software, of instant information movement, we still believe we’re living in the mechanical age of hardware. At the height of the mechanical age, man turned back to earlier centuries in search of “pastoral” values. The Renaissance and the Middle Ages were completely oriented toward Rome; Rome was oriented toward Greece, and the Greeks were oriented toward the pre-Homeric primitives. We reverse the old educational dictum of learning by proceeding from the familiar to the unfamiliar by going from the unfamiliar to the familiar, which is nothing more or less than the numbing mechanism that takes place whenever new media drastically extend our senses.

From “Marshall McLuhan in an interview with Eric Norden in March 1969”

This overhang from the past is why we describe new technologies in the form of the old. Steam engines were rated by their horsepower because they were replacing horses. So were the internal combustion engines that powered automobiles, trucks, and tractors that replaced horses. Lightbulbs were rated in candlepower for brightness.

The early for the automobile was the “horseless carriage” and the trade magazine for the industry was “The Horseless Age.” We are now dipping toes into the age of driverless cars. We relied on the telegraph and telephone for distance communication, early radio was referred to as “wireless” to distinguish it from the older technologies We have cordless phones in our homes and wireless phones we carry into the world in our pockets and cars.

Digital workflows are described as paperless. Digital or software-controlled locks are referred to as keyless (although I had combination locks on my gym locker and bicycle in the 1960s that did not need batteries or software. And let us now forget all of the terms influenced by E-Mail (electronic mail): E-book, E-commerce, E-learning, E-newsletter, E-signature, E-sports, and E-wallet. These are relatively well-understood terms, while artificial intelligence, artificial general intelligence, and (artificial) superintelligence remain moving targets that may be more marketing hype. Depending on how things work out, they may soon be roughly equivalent to terms like toxic or radioactive.

Normal, New, Unnatural

It’s hard to see what’s happening because we often lack accurate metaphors and models for the impact of technology on our lives and our culture. Even in our own lifetime our baseline perception is established in childhood. Douglas Adams offered a “normal, new, unnatural” framing for how we react to technology innovation

“I’ve come up with a set of rules that describe our reactions to technologies:

- Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

- Anything that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

- Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.”

The Past is All We Can See

This book [Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance] has a lot to say about Ancient Greek perspectives and their meaning but there is one perspective it misses. That is their view of time. They saw the future as something that came upon them from behind their backs with the past receding away before their eyes.

When you think about it, that’s a more accurate metaphor than our present one. Who really can face the future? All you can do is project from the past, even when the past shows that such projections are often wrong. And who really can forget the past? What else is there to know?

Ten years after the publication of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance the Ancient Greek perspective is certainly appropriate. What sort of future is coming up from behind I don’t really know. But the past, spread out ahead, dominates everything in sight.

Robert Pirsig in afterward to 10th anniversary edition of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1981)

An accurate understanding of the past gives you a very good sense of human behavior and culture. As Winston Churchill advised, “The farther backward you look, the farther forward you are likely to see.” I like the Greek metaphor of the future sneaking up on us from behind as we carefully study the past.

“Going forward into the future with only the past as our guide is akin to driving down a road with a blacked-out windshield and only a fleeting glimpse of the rear-view mirror to help us on our way. It is unfair that men should live thus; uncertain of their eternal fate; blinkered and ignorant even of the consequences of their well-intended actions. Perhaps the most we can hope for is to act with honesty and goodwill. Robert E. Lee is forgiven for choosing the wrong side; forgiven for his sincerity and manliness. Sherman is pardoned his brutality; pardoned him for being in the right. But the book has not yet been written of our days; yet tomorrow we shall write and be judged.”

Richard Fernandez in “The Rearview Mirror“

Closing Thought: “Who do we intend to be?”

Leadership is a function of questions. A leader’s first question is “Who do we intend to be?” not “What are going to do?”

Max De Pree

In the end, I think Warren Ellis got it right. The challenge is not just to see the future but to make it better. Sometimes, we see a possible future and try to prevent it: books like 1984, Brave New World, and Fahrenheit 451 were written to reduce the risk of society drifting into a bleak future. Despite our difficulties in predicting how new technologies will evolve or interact, our objective has to remain ensuring it is put to humane use.

Related Blog Posts

- Discerning the Future

- Quotes on Foresight

- Some Things Change, Others Remain Constant

- John Gardner: Leaders Detect and Act on the Weak Signals of the Future

- The Future, Arriving Yesterday, Remains In Constant Motion

- Harbinger or Outlier, Vision or Mirage, Threat or Opportunity

- End of Year Planning Checklist To Prepare For 2024 (Still useful for 2025)

- Jordan Peterson: Benchmark Yourself Against Your Past Self

Sources for Full McLuhan interview

Image source: 123rf.com/profile_niserin licensed from 123RF; Marshall McLuhan photograph is in the public domain.

This post was published on LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/marshall-mcluhan-how-see-future-sean-murphy-9opac/