A recent conversation between Micah Boster on market insertion. We discuss how B2B startups develop the right product for the right market, and manage the introduction.

Micah Boster on Market Insertion

What follows is an edited transcript of an extended conversation with Micah Boster on the challenges startups face in defining and managing product definition for a new market and managing the organizational and customer relationship challenges that flow from successful market insertion.

Sean Murphy: I am fortunate today to have the opportunity to take part in a discussion with Micah Boster on how B2B startups develop the right product for the right market, manage the introduction, and scale their organization as they meet with customer acceptance and escalating customer demand. This set of challenges goes by various names, such as market selection, new technology insertion, product-market fit, and disruption. We will compare experiences and lessons learned and see if we can offer some conclusions and suggestions for founders.

Micah, can you please introduce yourself and talk a little bit about what you are up to these days.

Micah Boster: Absolutely. Thanks, Sean. I’ve been in tech for about 20 years. I joined Google at the start of the SaaS revolution in 2007, where I was a very early member of their federal government enterprise team. I was there for about eight years, working across sales, strategy, partnerships, and roles in both the enterprise and core businesses.

In 2015, I left Google and moved back East. Over the past decade in New York City, I’ve worked with early-stage startups in a variety of roles: COO, VP of Operations, Head of Partnerships, and often serving as the “VP of Common Sense.” Essentially, I’ve been the person who understands how things work, how to get things done, and what steps are needed to get from point A to point B.

For the last four years, I ran operations at an AI startup in New York City. In December, I left to start my own venture, launching Nighthawk Advisors in April. Our focus is on addressing a few key issues I’ve observed in the market:

First, it’s become significantly harder to raise money than a few years ago. The “dumb money” has largely left the market, leaving professionals who expect you to deliver on your promises and meet timelines. The era of taking two years to find product-market fit is over—you’re expected to execute and produce results much faster.

Second, startups have always struggled with execution. I help founders tackle these challenges: establishing operations, defining their goals, setting measurable milestones, and tracking progress to ensure they stay on course. Many founders chase shiny objects, spin their wheels, or burn through cash unnecessarily because they haven’t taken a step back to assess how they’re operating or what they’re trying to achieve.

I’m based in the New York City area but work with people worldwide. It’s been incredibly rewarding to help companies figure out how to run more effectively, achieve their goals, and ultimately build the businesses they envision. It’s been super fun and fulfilling.

Sean Murphy: Cool. I’ve been working with bootstrappers since around 2003. I tend to focus on an earlier stage in the primordial soup of entrepreneurship—where we’re trying to figure out if we can find something that works. The goal is to get them stood up enough to execute somewhat reliably.

So, as a thesis, you mentioned there’s been a lot of dilettantism: at least during the zero-interest-rate regime, there were plenty of dilettantes. Many of them may have exited the landscape now.

Don’t Lose Focus on Providing Value To Customers

Micah Boster: I’ve seen this in companies I’ve worked for and in some I’ve advised—particularly with companies that start with technology rather than domain expertise. Often, people are so focused on the technology itself that they neglect the details of the industry they’re targeting. To put it another way, there’s so much emphasis on “bringing disruption to the table”—to use a VC buzzword—that they lose sight of how to achieve that disruption effectively within their chosen industry.

I’ve seen this play out in companies where neither the leadership team nor the product team had experience in the industry they were targeting. Instead, they relied on outside advisors and broad assumptions, which weren’t necessarily informed by deep industry knowledge. This becomes especially problematic in today’s environment, where execution is critical and delivering results is non-negotiable. I think that you particularly run the risk of this in companies that are tech-driven and focused around a specific innovation or application, where there’s a bit of stumbling around trying to find the right industry and the right problem without a deep understanding of any of them.

The tech and startup world has matured and become incredibly crowded. While there’s still low-hanging fruit, many real opportunities are in niches—specific parts of industries with unique problems that aren’t immediately visible to outsiders. These are challenges that people within the industry deal with regularly but might not be apparent from the outside.

Broadly, I’d like to discuss how startups can approach their product development and business strategy in a way that brings real value and traction. This involves digging deeper into the nuances of the industry, combining the tech-first disruptive mindset that VCs have championed for years with genuine, industry-focused problem-solving.

Sean Murphy: A team approaching an industry with “newcomer eyes” can have a strong advantage, especially when they are leveraging a technology that has matured elsewhere and is now finding its third, fourth, or fifth use. In these cases, the focus shifts from solving fundamental technology issues to customization and application.

So, initially, a team without an insider perspective is not necessarily headed for disaster. They can make progress if they have a working technology, a supportive community, and a hypothesis about how it might impact an existing industry. However—and I think you’re also making this point—they need binocular vision. They must understand what’s happening outside their target industry while incorporating deep insider knowledge.

The challenge is how these teams attract, incorporate, or blend the insider perspective—those with deep industry experience—with the “newcomer eyes” approach. How have you seen teams successfully recruit or integrate individuals with an insider or old-timer perspective into their organizations? How do they balance these two points of view effectively?

Micah Boster: I think there are two ways to approach this. We’re now in a world of vertical SaaS and vertical AI, where more companies are tackling specific domains. Some of these new companies take well-defined technology ideas from other areas and apply them to industries they know deeply.

This approach wasn’t always the most common in the zero-interest-rate world. Over the last 15 years, there’s been an emphasis on avoiding being confined to niche markets, but that seems to be shifting now.

The other thing I’m seeing more of is companies bringing in domain experts at the product level, even when leadership may not have the experience themselves. Even if the executive team is primarily focused on big-picture visions of change and disruption, they’re complementing that with product owners who know the space well. These people understand the users’ workflows, know where the pain points are, and can identify where the product will deliver real value. By integrating this insider perspective, they can better align the vision with the practical needs of their target users.

Stepping Across the Table: How Do Prospects Evaluate A Startup’s Promise?

Sean Murphy: If I’m a customer trying to assess two or three companies bringing different technologies—or different aspects of the same fundamental technology stream—to my industry, how do I evaluate them? In your model, I might talk to the CEO, who seems energetic, visionary, and passionate but doesn’t seem to understand much about my day-to-day operations. But then I talk to a product person who has a much better grasp of the practical realities.

How do I know that the natural tension between the product and executive teams will be resolved in a way that serves me? A year from now, after taking this journey with them, how can I be confident I’ll end up with a solution that meets my needs rather than one that simply fulfills the founder’s vision?

Micah Boster: That’s always the challenge with startups, right? The question is: where is this going? I think most companies entering complicated or crowded industries differentiate themselves in some way. For example, they might focus on a specific part of the workflow as their primary target or go after a very particular customer set.

Some companies position themselves as catering to experts, offering highly customizable products with APIs and the flexibility to build exactly what you need. Others take the opposite approach, targeting users who want simplicity—automating everything, smoothing workflows, and minimizing complexity.

The key is to pay attention to where the company’s focus is and the kinds of things they’re saying they want to do. That will give you insight into whether their direction aligns with your needs and expectations.

Sean Murphy: Are there tests a prospect could use to question the startup’s “VP of Common Sense?” They might say, “Well, we haven’t hired that guy yet,” or “We had one, but we couldn’t hang onto him: he became so frustrated he left.” You are presenting a scenario like the scene in Pulp Fiction where they open the box, and this bright light illuminates the awe-struck faces of the people who get a look inside. But then, as a customer, you realize that no matter how tempting the demo is, you don’t get married after one or two great dates. And you ask what’s in it, and they answer, “The substance in this vessel is very powerful and promotes growth.” How do you tell you are not looking at a crock of manure?”

Micah Boster: Exactly. And especially in today’s environment, you must listen to what companies are saying and their ambitions. It comes down to understanding how a company sees itself, what it’s trying to build, and the vision it’s working toward. I’d be very skeptical if executives can’t articulate that vision or show a roadmap. Buying enterprise software from small or upstart companies is hard enough—you don’t know if they’ll even be in business a year from now. But if they’re not focused on solving the problems you care about or moving in a direction aligned with your goals, they’re certainly not going to be helpful.

Micah Boster: Exactly. And especially in today’s environment, you must listen to what companies are saying and their ambitions. It comes down to understanding how a company sees itself, what it’s trying to build, and the vision it’s working toward. I’d be very skeptical if executives can’t articulate that vision or show a roadmap. Buying enterprise software from small or upstart companies is hard enough—you don’t know if they’ll even be in business a year from now. But if they’re not focused on solving the problems you care about or moving in a direction aligned with your goals, they’re certainly not going to be helpful.

Every company has a focus, a way they differentiate themselves in a crowded market. You need to look at what they’re doing and determine whether it aligns with what you’re trying to achieve.

Another point that follows from your question is that customers often don’t fully know what they want. They just know they have a problem. The more clarity you bring to the table about the solutions you’re looking for and the problems you need to solve—not just today but long-term, in terms of workflows and processes—the better off you’ll be.

I put together a set of questions to help companies navigate the challenges of understanding the customer’s current solutions, workflows, and related economics. Your answers will give you a quick sense of what you know and where more research may be needed. They can be used by folks inside startups working on their go-to-market and positioning, as well as by buyers starting their evaluation process. Like everything, this is a heuristic, but I find these types of questions to be pretty helpful in understanding the depth of understanding and market positioning.

Sean Murphy: That’s work worth doing. So, two questions. Let’s say I’m the visionary CTO or CEO, and I have a strong hypothesis or belief that this capability or technology will have an impact on this industry. I hire a product person from this industry, and we start engaging with customers with established operations and some scale.

Given your earlier point that customers often lack a clear vision of a solution, how do I thread the needle between offering something valuable to these early customers while ensuring it’s scalable for a broader market? I see two challenges here:

- Escaping nostalgia: How do I ensure I haven’t hired a product person who’s too focused on recreating the last product they worked on rather than innovating for this opportunity??

- Avoiding bespoke solutions: How do I prevent customers from pushing for a tailored solution that locks me into their specific needs rather than allowing me to create something scalable and applicable to others?

How do I navigate these challenges effectively?

Plugging Into Existing Workflows More Likely to Succeed Than Rip-and-Replace

Micah Boster: I think this is where specificity and understanding the industry become especially critical. The way to truly connect with customers is by solving a real and specific problem in a clear, tangible way. It’s something go-to-market teams need to repeat to themselves over and over again.

Micah Boster: I think this is where specificity and understanding the industry become especially critical. The way to truly connect with customers is by solving a real and specific problem in a clear, tangible way. It’s something go-to-market teams need to repeat to themselves over and over again.

For context, remember that it’s really hard to sell “rip-and-replace” of an existing product in enterprise software —nobody wants to pull out their existing systems and start over. If that’s your market entry thesis, you’re starting behind the eight ball. What customers WILL do is slot something in that solves a specific problem.

So instead of telling your prospects, “We have this brand-new tool with a whole new console and dashboard, and it’s going to give you information you’ll have to figure out how to use,” you should approach it like this: “Here’s your current workflow—you move your leads from point A to point B, track analytics in system C, and it’s really hard to get a report that ties these three things together. We solve that problem. Let me show you how, and let me show you how this can integrate tomorrow to make your team’s life easier.”

It’s about bringing real value to the table. That value comes from deeply understanding the problem set your users—whether analysts, managers, or operators—face and addressing it specifically. You can expand your offering later, but as a startup, especially in the B2B software space, specificity in problem-solving is essential.

This requires understanding industry workflows, the standard tools people use, and the factors they consider when choosing them. Building into an existing ecosystem can be a smart approach. For example, maybe you create a solution that integrates with Salesforce, Tableau, or another widely used platform. Instead of asking people to change their systems, you enhance them.

By solving one specific problem well, you gain credibility. From there, you can solve another problem, then another, and continue to grow incrementally. I understand this isn’t novel stuff, but it’s important, and it’s something a lot of early-stage companies lose sight of with all the pressures they have.

Sean Murphy: Your suggestion to offer an add on or plug in–or what the IT guys you are selling against if your target is an unhappy department manager would call a “wart”–gets you to market faster and offers some other advantages. Because it’s smaller it’s more testable both from a software development perspective and as a simple value proposition. It’s more continuous with current practice because it replaces much less than what we used to call a “forklift upgrade” where an entire new system is dropped in. And it’s normally lower cost as a result which allows you to sell lower and use up less of your buyer’s budget and organizational or political capital.

Change is Slow. Big Change is Hard.

Micah Boster: After 20 years in enterprise software, my general view is that change is slow, and big change is hard. If you’re trying to sell to medium to enterprise-scale companies, there will always be a lot of politics. I’m a big fan of getting done what you actually can get done and delivering real value as a way of establishing credibility. I think you can always build from there.

If your startup has solved one pain-in-the-ass problem really well, customers will talk to you about all the other stuff they want you to do. But you must do something well first, and that’s usually a compact and specific problem.

Look, some startups are swinging for the fences that should be. They have brand-new technology or an entirely different way of looking at the world. But it’s not most startups, certainly not most of those getting funding today.

I think we’re in a world right now with a lot of vertical SaaS and vertical AI applications. We’re seeing many people trying to get into the guts of an industry and solve a specific problem. My basic point is that if you’re going to do that successfully, you need to understand the industry so you can speak the language and position yourself correctly to deliver value.

Sean Murphy: My take on your insertion point or finding someone with a problem is that you must be more cautious when replacing a custom internal solution than when adding onto a commercial product already accepted in the market. It’s less likely to result in an idiosyncratic solution with a market of one.

That’s also why you’re better off finding three mid-size players who agree on a need rather than a single large firm that you hope will act as a “lighthouse customer.” Implementing in parallel and managing three parallel sales and implementation processes is a lot more work, but it helps prevent you from inadvertently becoming a custom software supplier. Otherwise, you may allocate future support and updates against a much narrower payoff than you’d get with a niche market product.

A critical amount of what’s called “requisite variety” in a different context makes it far more likely that you’ve discovered a true niche.

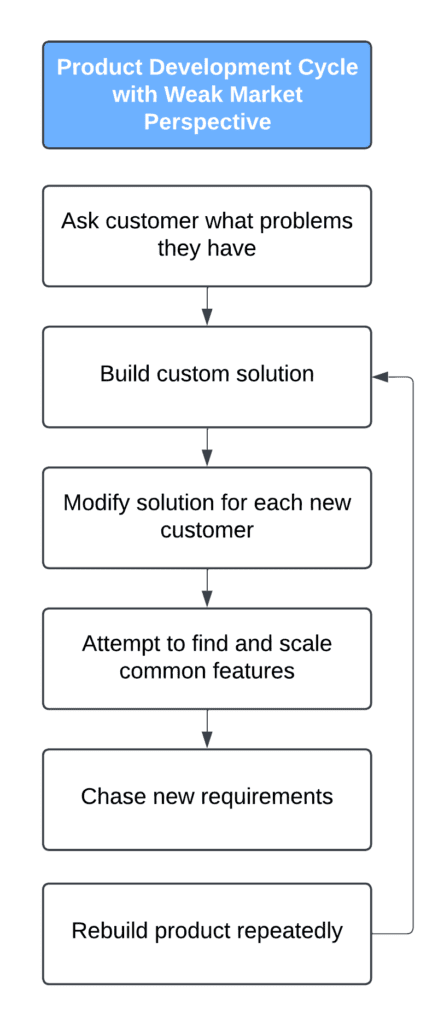

Micah Boster: Yep exactly! We’ve seen a ton of this over the past few years in the AI space, where companies implemented custom solutions in the hopes of scaling into some kind of platform play that they could then productize and resell. Most of them didn’t pull it off because it’s really hard to avoid, as you said, turning into a custom software company. These companies started by going into enterprise companies and asking, “What can we help you with? Where are your problems?” You’re rarely going to find a general solution with that approach.

The assumption was always that they’d productize and license it to others afterward. But other companies might not have the same problem—or not in the same way. Inevitably, you go too far down the customization route and can’t dial it back. Then you run into issues where customers want exclusivity or ownership of the IP because they feel like they co-developed it with you.

This is why I think a nuanced, solution-focused approach is so helpful. It allows you to dictate the terms of product development differently. You can come in and say, “We have a solution to this problem—let us do this for you.” Then, if there’s interest in deeper customization with that specific company, you can explore it later. At least you’ll have a scalable product to bring to market and won’t waste all your time building something you can’t sell to anyone else.

Bootstrappers Can Lose the “Develop Once, Sell Many Times” Perspective

Sean Murphy: Bootstrappers are definitely at risk for this. Especially if they have worked as freelance software developers or in an internal IT function, they can fall back into old patterns and lose the perspective of developing once and selling many times. If you force yourself to solve more or less the same problem for several customers in parallel, you pull forward some of the priority conflicts you’re going to face.. It’s more complicated and often a little slower, but you make the conflicts and priorities you will need to balance much clearer, making it harder to go too deeply into something you can’t pull out of.

Micah Boster: Yeah, it also requires that you have internal expertise within your company. In many ways, the custom model we just discussed has put many companies in a position where they’re essentially doing industry discovery—learning about the industry’s problem set—through the customer they’re building a custom solution for rather than bringing their own perspective to the customer.

Sean Murphy: You advocated that, at a minimum, the product guy should have some industry or domain expertise. But the founders may make the mistake of telling themselves, “We have technology expertise, we don’t need domain expertise. We’re just going to go listen to this internal guy who loves to work with us and has got a big budget.” They can end up delighting one person who is not representative of a larger problem and getting trapped in commitments that take resources away from larger opportunities

Micah Boster: That’s right, and even worse, you can checkmate yourself from a business model perspective if you don’t think this all out. Inevitably—and I know this because I’ve done it about ten times—you end up in tough negotiations with the customers you’re building custom stuff for around exclusivity and licensing rights and end up with serious restrictions on who else you can sell to. It’s tough to convince a customer to pay you to develop something based on their needs and specifications and then allow you to turn around and sell it to their competitors. The contract language you may have to accept can make it impossible to scale effectively in the vertical you’re pursuing, which limits you even more.

If you don’t do your homework and bring your own perspective to the table, you give up a lot of your leverage. You also lose the ability to walk away. If you go too far down the rabbit hole with a customer, building something that’s essentially a semi-custom solution, you can end up completely tied to them.

Co-Development Based Product Strategies Carry a Lot of Risk

Sean Murphy: If a customer is more than a third of your revenue, it becomes hard to say no because losing them is too significant. Paradoxically, it’s often easier to get more business from them in the near term than prospecting elsewhere, so it becomes easier to let them become more and more of your revenue.

Micah Boster: Right! If you have a product you’re bringing to the table—not something you’re co-developing—it’s a much more straightforward approach. “Do you want to buy what we’ve got? Yes? No? No? Cool, we’ll go to the next person and ask them.”

In my opinion, getting to a real product is critical for most small companies trying to establish themselves. It’s really hard to achieve that if you don’t have sufficient internal industry perspective and credibility to drive the conversation. That brings it back around to the beginning.

Sean Murphy: One thing I’ve seen help sometimes is focusing on smaller companies that are in real agony—those who are more motivated to find a solution and change their business.

The second thing is starting some kind of customer advisory group or roundtable. You bring in your first three, six, or nine customers—it doesn’t work as well if you go beyond a certain threshold—and let them argue with each other. This approach can help hammer out, in theory, what they want to rely on you for versus what they’ll still customize or implement on their own.

Micah Boster I would argue two things. First, you still need industry knowledge and credibility to run a successful working group. For one, you need to have developed enough of a product to get six customers to sign on. At that point, the group should be debating the last 20% of features—questions like, “Do we need to connect to this database?” or “Do we need to build a different API framework?” These are more usability questions than foundational ones.

Second, without industry credibility, it’s going to be very hard to get multiple customers to engage in a working group at all. That’s a critical barrier to making this approach work.

Sean Murphy: You make good points. If you can at least be in discussion with two or three prospects, you are less likely to develop a custom solution accidentally. While you need your own product vision, I think customers play a critical role in shaping that direction. However, startups are sometimes reluctant to “open the kimono” and let their customers argue it out. Instead, they position themselves as the ping-pong ball, running between customers rather than facilitating direct conversations or collaboration. When you don’t let your customers negotiate with each other and come to a shared understanding of what they want in a product, I think you risk the “short order cook” failure mode, where you lapse into an outsourced software development model or feature factory.

I like your idea of avoiding a “rip up and replace” approach by offering a narrow solution with clear integration points: a plugin. It’s not always clear how to expand or what “Act Two” looks like after an initial success. Once you’re established, you can often go in a dozen different directions. How do you help teams decide?

Better to Start with a Narrow Focus and Spread Out Over Time

Micah Boster: I think startups can cultivate robust customer ecosystems when they offer a clearly defined vision for their product. Customers usually focus on usability questions, integration issues, and similar concerns.

That said, I am not arguing that a plugin or narrow solution model has to be the end of the company’s product vision. A narrow solution can serve as a beachhead while the company develops a longer-term, broader strategy. How you choose to engage customers in the initial solution, long-term development goals, and your overarching vision is entirely up to you.

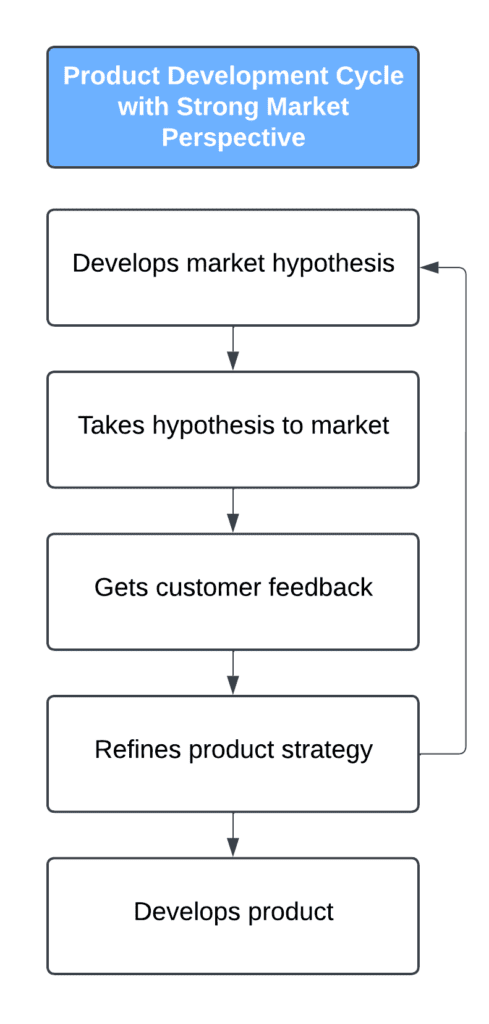

Fundamentally, your go-to-market efforts become much more effective when you have a clear vision to bring to the table. You still have to listen as you engage customers so that you can use their experience and insights to refine and shape your strategy.

Another issue I’ve seen, depending on the sale, is that even within a big organization, different stakeholders and departments often have conflicting needs. If you’re not clear about who you’re selling to and why, it’s easy to get pulled in different directions. For example, the finance team might say, “We’d really like it if it did this thing,” but you have to recognize when that’s not aligned with your vision—especially if they’re the only ones asking for it.

Ultimately, I think this all ties back to having industry expertise. In my view, that’s shorthand for having a clean, well-defined product vision that clearly specifies how you want to position yourself in the market and what you want to be in that market.

Sean Murphy: I buy into that approach. Let me ask you about the following challenge. When you form that vision you have the collective expertise of the founders and your product folks. And you use that to define goals and set a direction.

Micah Boster: Yes, you plant a flag and march toward it.

Sean Murphy : As you build that vision out and talk to more customers you learn more, gather additional evidence, some of it contradictory. And by definition when you planted the flag you had less information than you do after engaging with the market.

Micah Boster: You should absolutely be updating your plan as you go.

Sean Murphy: So now the founders have built a larger term and hired a VP of Common Sense to help with scaling and operational excellence. Does that VP ever blow the whistle and say, “wait a minute, we may have the flag in the wrong place.” What are your rules of thumb for managing the changes to your vision and action plan?

Execute Based on a Deep Understanding of Customer Needs, Recalibrate as Needed

Micah Boster: The way I think about an execution framework is pretty simple. You start with a vision, set goals to support that vision, resource against those goals, and establish KPIs to track progress. But the most important part is having a mechanism to recalibrate based on the data you’re seeing.

This recalibration has two aspects. First, there’s hard data: for example, if the people you expected to buy aren’t buying or users aren’t engaging with certain functionalities as anticipated, you need to adjust accordingly. Second, there’s the opportunity to engage in dialogue with customers.

In the context of a customer roundtable or working group, your product team isn’t doing their job if they’re not taking customer feedback seriously and interrogating the product timeline and roadmap based on what they’re learning. You absolutely need to commit to the market, but that commitment should be informed by what you’re observing and hearing.

Sean Murphy: We work with small teams, typically two to five, but normally less than a dozen. Everyone can fit around one table. They make many small, frequent adjustments based on recent sales calls, customer support calls, and what they learn from partners. But how often do you recalibrate in the larger firms you work with? I would assume there are more delays involved in collecting information and making decisions. What are your rules of thumb for moving the flag or adjusting the next waypoint of the march?

Micah Boster: Like everything, there’s an art and a science about it. We reassess if we’re consistently missing our targets in the data – our numbers are off, we’re missing deliverables, whatever. In that case, you need to look hard at what’s off – is it execution, or are the goals wrong? Especially at the beginning, some of your goals may be wildly optimistic or wind up being trivially small. You’ll need to adjust. But I think this is where good leaders must check in with their team. Are the folks on the ground telling you things they’re hearing from the market? Are you dropping off in a certain part of the sales cycle? Is one of your competitors catching fire? It’s worth reassessing then, too. Goals aren’t prisons; your short-term goals should be revised if they aren’t moving you closer to your long-term goals. They shouldn’t lock you into something that’s not working. You have to respond to reality and figure out the balance between pushing your team and being realistic about what’s achievable.

Sean Murphy: That makes sense.

Micah Boster: I wanted to make one more point. We talked a little earlier about the fact that getting pulled too deeply into a single customer can screw up your commercial approach. It also can totally destabilize your entire product development process in ways that are really hard to fix later.

Here’s the thing. You’re always going to need to get market feedback. That’s basic customer success – talk to your customers, deliver things they want, fix their problems, whatever. But what can happen if you don’t understand your market well enough or your customer specifically enough is that you end up looking to customers not only for feedback but also for product direction. Instead of taking a product hypothesis to the market and having customers use it and give you feedback, you go to the market in search of a hypothesis. It puts companies in a position where their product strategy is driven by custom work, which is rarely optimal for scaling into a real product. We talked earlier about how many first-gen AI companies had this problem – they had cool tech and went around to enterprise customers, essentially asking, “What problem do you need solved?” They always intended to scale the custom work into a product and then sell it to similar customers. But because they focused so much on their customers’ needs, they never developed the strong market perspective they needed within their product and go-to-market teams, making it even harder to chart a sustainable path forward. They ended up focused on how to sell the thing they had built and didn’t have the people or the processes to ask if the thing they built was the right thing or not.

Make sure you are bringing an informed perspective to the market and aren’t going to the market looking for a perspective. The checklist we have linked has some good questions to ask yourself to ensure you have the right plan. If you don’t, look at your leadership team and your product roadmap and do the work.

Sean Murphy: Micah I want to thank you for your time and your insights. You have a lot of experience that allows you to provide a well-founded perspective on the challenges of bringing new products to market and scaling your organization to handle success.

About Micah Boster and Nighthawk Advisors

Micah Boster is the founder of Nighthawk Advisors. He is a business advisor with 20 years of experience helping early-stage SaaS and AI startups thrive. Previously, he spent eight years at Google and ten years at early-stage NYC-based startups leading revenue and operations functions. He holds a BS in Symbolic Systems from Stanford and an MBA from INSEAD.

Nighthawk Advisors provides advisory, executive coaching and fractional COO services to Series A and B companies preparing for or experiencing explosive growth. They focus on improving process, planning and accountability as part of a coherent business operating system with a specific focus on keeping things simple, useful and transparent. Based in New York, they support clients in SaaS, AI and Financial Services across the globe.

Micah Boster – Market Understanding and Differentiation Assessment Questions

Related Blog Posts

- The Science of Targeting: How Startups Select the Perfect Niche

- Key Questions to Answer Before Adding A Feature to Niche Software

- Preserving Trust And Demonstrating Expertise Unlocks Demanding Niche Markets

- Worry About Scaling After You Find Your Niche

- Newsletter August 2024: Startup’s Mission

- A Common MVP Evolution: Service to System Integration to Product

- Office Hours: Schedule Time to Review Your MVP Readiness

- Prep for 2025: Bootcamps on Customer Discovery & Development

Image Credit: “Product Development Cycle with Strong Market Perspective” and “Product Development Cycle with Weak Market Perspective” (c) 2025 Micah Boster, used with permission.

This was republished on LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/qa-micah-boster-market-insertion-sean-murphy-u9cfc